From Easter to November first the same number of psalms laid down above is to be said.

How do you remember all those lines?

We remain here at the Divine Office of Matins or ‘Vigils’ for another chapter; this one slightly shorter than the other two and, on the face of it, with little to be added to the reflections on this particular activity. There are two things, however, which stand out for me: the memorising of the readings and the real importance of the psalms.

As a theatre practitioner from an early age, learning texts to recite/perform is second nature to me now (a line from My Fair Lady, which goes to show how quickly I can recall scripts!) I have spent the last eight years learning bits of Scripture to ‘present’ in worship services at different times. From Genesis to Acts, Ruth, the Gospels and most recently, Jonah. It doesn’t take me long to get the text in my head (although it is taking longer the busier my mind gets) all I need is a dedicated hour or so for long passages.

I enjoy working through a passage and studying the original meaning and translating it into a modern context. I rarely change words from the translation that is given and when I do it is a deliberate choice made to get a particular point across. I’d rather use the words in the translation and use tone and inflection to communicate meaning and I say that because meaning and interpretation should always be held in a state open to questions but the words, for me, must remain relatively static.

The benefit of learning Scripture is manifold. I want to just speak on two for now.

I’m sure that I am not alone in the experience of listening to the Bible being read in Church services and feeling bored to the point of death. Well meaning and faithful Christians get up to the front with a bible in hand and in a monotone and sombre voice begin to speak the words on the page in the order that they have been written, sometimes noting punctuation but often not. Is it any wonder many people are not inspired to read this book if the people who apparently are meant to receive the revelation of God Almighty through it are so down beat and depressed by it!

I’m always surprised when Christians don’t want to read the Bible but I can understand their view when it is presented in a dry and tedious fashion. Yes it is confusing at some points, yes there are passages which challenge and others which are just a list of names but if your starting impression of this book is that it is complicated, dry and difficult to stay awake to then I wouldn’t pick it up. It’s like me and War and Peace; I know I should read it but the impression I get is it’s just a long book which is difficult to read. That impression is a big stumbling block for me.

I learn the Scripture by heart so that I can tell the story of God and His people in a way that may inspire people to pick up the book and carry on reading. If I am not concerned with making sure the sentences make sense and I say the right thing then I am free to look people in the eyes and tell them this story like I’d tell them any exciting tale from my life or someone else’s.

When I work with people to help and encourage them to develop their reading style I’ll often suggest two exercises: imagine this story happened to you or that what you’re telling people is something you believe in and then go through the text and mark out the kay words or phrases which people should be able to remember after you’ve finished. We forget, in the fear of perceived failure and weight of expectation, that the Bible is life giving. The words reveal the character of God. If we read the Bible and people feel bored and unconnected to what you’re saying then that’s the impression they’ll get of God. For me lifting our eyes and connecting with people, telling this story like we tell other stories such as what we did yesterday or a memorable day from our pasts captures people and they live it again with us.

The second benefit of learning Scripture is more important than the last: so ‘the word of Christ dwell in you richly.’ (Colossians 3:16) I don’t remember all the passages, word for word, that I have memorised but I remember key phrases and the meaning of them. I recall them when I accidentally use similar phrases in life. When I am trying to talk about God I find phrases and passages coming to mind and I am better able to use them in everyday life. Having a general knowledge of different texts also helps when struggling with passages in the Bible; you’re able to better balance and compare ideas and bring the story together. This protects against taking verses out of context or using them falsely.

In this time of Lent it is useful to follow Christ into the desert of temptation and, like Him, use Scripture to defend against the lies and deceits of the Devil who will, as he did in the Garden of Eden take what we think God says and twist it. To be able to quote God and, through wisdom, know it’s meaning is a weapon against the powers of darkness that will seek to confuse us as to who and God is like. The devil tries to soften us to make God in our own image, to become certain that God is what we think He’s like rather than allowing the true God to reveal His perfect character to us.

After I present a passage of Scripture from heart there’s one response that is predictable,

How do you remember all those lines?

It is disheartening. Why? Because it’s the wrong question. It makes me feel like that what I was doing was showing off a party trick rather than being helpful in engaging people with the revelation of God. I consider packing the whole thing in and not bothering because people are so distracted that I can memorise something like a country fair exhibit that they’re no more inspired by the words that I was speaking.

So for all of you who watch any performance where an actor or performer learns lines off by heart here is the answer to that question: They picture the words on the page, or they connect certain words with actions, or they learn the words to a rhythm or tune. We all remember things; pin numbers, song lyrics, sequences of events, names, faces, etc. We do it because we care about them or they are important. Actors learn lines because they’re important. It is a skill which anyone can learn given the time and dedication. It is a discipline and I encourage you all to try to do it with Scripture.

After you see someone do such a ‘feat’ and you feel you want to say something to them afterwards, don’t say ‘How do you learn all those lines?’ Rather talk them about the words they have spoken, the tone of voice they chose, their interpretation and engage them in a conversation about their process. Ask them,

What did you learn from all those lines?

The Book of Psalms

It is interesting to me that, between ‘Easter and November first’, with the shortened time between midnight and sunrise, St. Benedict chooses to cut the number of readings down to one short passage (memorised) and not cut the number of psalms said. Twelve is a large number of Psalms particularly for slightly longer ones. What is so special about the Psalms?

Abbott Philip Lawrence, OSB notes,

The number 12 is very important in the history of monasticism because a tradition that an angel appeared to Saint Pachomius and revealed to him the importance of praying 12 psalms. (Philip Lawrence, “Chapter 10: The Arrangement of the Night Office in Summer”, Benedictine Abbey of Christ in the Desert, March 11 2014, http://christdesert.org/Detailed/880.html)

Thomas Merton puts the grand-ness of the psalms well when he writes,

To put it very plainly: the Church loves the Psalms because in them she sings of her experience of God, of her union with the Incarnate Word, of her contemplation of God in the Mystery of Christ. (Thomas Merton, ‘Praying the Psalms’ (Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1956) p.9)

The Psalms are not just about what we say and what we get out of them but there’s an element in which our prayers are replaced by the prayers of the Other. For Merton it is the Church and God. Dietrich Bonhoeefer puts it nicely when he says,

The Psalter is the prayer of Christ for his Church in which he stands in for us and prays in our behalf … In the Psalter we learn to pray on the basis of Christ’s own prayer [and] as such is the great school of prayer. (Dietrich Bonhoeffer, ‘The Psalms: The Prayer Book of the Bible’ (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 1970))

In some psalms it is easier to see and experience this than others. Walter Brueggemann, another great scholar and theologian whose book on the psalms is well worth reading, says this about those more difficult psalms,

Much Christian piety and spirituality is romantic and unreal in its positiveness. As children of the Enlightenment, we have censored and selected around the voice of darkness and disorientation, seeking to go from strength to strength, from victory to victory. But such a way not only ignores the Psalms; it is a lie in terms of our experience. (Walter Brueggemann, ‘The Message of the Psalms’ (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing, 1984) p.11)

This morning in Northumbria Community’s Morning Prayer we read Psalm 94 which begins,

O Lord, you God of vengeance, you God of vengeance shine forth.

Rise up, O Judge of the earth; give the proud what they deserve.

My father in law once said that all the psalms seem to say,

God is good… now kill all my enemies.

I am regularly needing to edit down Psalm 139, which I use at funerals, because no one, at a time of sorrow and loss, needs to hear,

O that you would kill the wicked, O God, and that the bloodthirsty would depart from me… I hate them with perfect hatred; I count them my enemies.

How is reading, let alone praying, these psalms allowing Christ to pray through us? How are we being shaped into the likeness of Christ by speaking these desires out? Brueggemann suggests,

By the end of such a Psalm, the cry for vengeance is not resolved. The rage is not removed. But it has been dramatically transformed by the double step of owning and yielding. (Walter Brueggemann, Praying the Psalms (Minnesota: Saint Marys’s Press, 1982) p.68)

Brueggemann also gave a series of talks on the psalms and here is a link to a video which sums up his view, which I think is helpful.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rDfzzJD8IpI

St. Benedict is clear that the ordained men and women of the Church should be, with Christ, praying on behalf of the Church. It is more important that we are interceding, coming between God and His people and acting as a bridge and a link; not with our own agendas and desires but being cleared to be pure channels of God’s grace into His Church. This is our role, not to grow in our inner life within a holy huddle, cloistered and protected from others but that we do the task of contemplation on behalf of the whole Church. Prayer is a task not a luxury (although we hope that it is both.)

Reflection

Despite being a small chapter it has thrown up two very practical challenges for me as I start Lent.

1. Why is it that I only learn Scripture when I am presenting it in public? How can I develop a practice of learning Scripture for the benefit of my own spiritual development, for protection against temptation?

2. How can I better develop my reading of the Psalms as the basis of my prayer life for the benefit of Christ’s Church? Where are the Psalms within the life of the parish church? Is there scope within Burning Fences where the psalms could be used in a creative way to express some of our spirituality?

I did start to try and learn the psalms off by heart (following the example of St. Aidan and many other celtic saints) but struggled. I think they need music to help me remember them and pray them as I travel round. I looked for some CDs of complete set of Psalms being sung but I never found anything. If any of you lovely readers fancy getting me a gift then that would be nice!

Christ, you prayed the psalms for Your people and so I join with You. Teach me to pray.

Come, Lord Jesus.

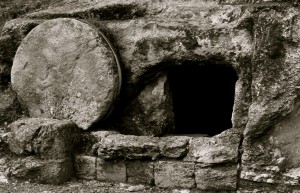

On Resurrection Sunday, I preached a sermon on the empty tomb and proposed that we can fall into the trap of staying at the empty tomb; we can get caught up in the empty tomb and be so amazed at it’s emptiness that we forget the real wonder of that day (This was an unashamed re-working of Thomas Merton’s reflection in his book ‘He Is Risen’). The empty tomb, I suggested, is just a signpost to the real thing. It is not the empty tomb we worship, it is the risen Lord. I likened this to gathering round a signpost for Yorkshire and celebrating as if we had arrived in God’s own country (I apologise to those heretics who do not accept this truth to be self-evident!)

On Resurrection Sunday, I preached a sermon on the empty tomb and proposed that we can fall into the trap of staying at the empty tomb; we can get caught up in the empty tomb and be so amazed at it’s emptiness that we forget the real wonder of that day (This was an unashamed re-working of Thomas Merton’s reflection in his book ‘He Is Risen’). The empty tomb, I suggested, is just a signpost to the real thing. It is not the empty tomb we worship, it is the risen Lord. I likened this to gathering round a signpost for Yorkshire and celebrating as if we had arrived in God’s own country (I apologise to those heretics who do not accept this truth to be self-evident!)

24. What is an encounter with the ‘hidden’ God like?

24. What is an encounter with the ‘hidden’ God like?