If the cause of the sin is secret (hidden in the soul), the monk should confess to the abbot or one of the spiritual fathers.

Who can I tell?

When the Lord comes,

he will bring to light the things now hidden in darkness,

and will disclose the purposes of the heart.

Therefore in the light of Christ let us confess our sins.

This is a seasonal provision in Common Worship for an invitation to confession from the First Sunday of Advent until Christmas Eve. I’ve been saying this for four weeks as I’ve led services in different contexts. The wording is from 1 Corinthians 4:5 and is a great image of bringing everything into the light.

Darkness, after the initial shock, can be quite comforting. No one can see what you’re doing and so no one can judge your behaviour. You are alone with your thoughts and those probing eyes of others are gone; you can do whatever you like. You’re free. Darkness brings this sense of privacy where you feel in control, released from judgement.

Darkness is also scary, isolating and lonely. With no sense of sight your other senses are heightened and, those of us who are reliant on our eyes most of the time, struggle to interpret the sounds, smells and other sensations that we are now aware of.

I’ve been involved in many a party game where someone is blindfolded and asked to feel an object and guess what it is. Part of the thrill or anxiety that is created is the unknown, the unseen. What if the worst thing imaginable is placed into our hands? Not knowing what the object is means you cannot prepare yourself for the possible movement of the object or the danger that it might be. There’s a great wave of relief when you see, even if you don’t like it, what the object was. When it comes into the light there’s a fuller understanding of what it is you were dealing with.

St. Benedict has returned to discussing issues of mistakes, faults and offences in community life. We all make them, they all have an impact beyond ourselves and we should all be prepared to admit them and try and make amends. In this chapter St. Benedict reminds us again that there is no difference between what happens in the ‘sacred’ to what happens in the ‘mundane’; we are to behave in the kitchen, cellar, garden, bakery, refectory, etc. as we do in the chapel/oratory. If we make a mistake or offend God or neighbour then we should treat it as if we did it in a ‘sacred’ space such as a church building. We are to go and make a public admission in front of abbot and the community so that no one is left in the dark over such matters.

Like the previous chapter, we are encouraged to admit quickly before the issue becomes larger by deceit and covering over the fault. It is easy to try and keep mistakes private out of fear of being seen to have failed and stumbled but greater is the shame if you are found to be using the darkness to cover such mistakes. The darkness is easy to use as a tool to select what others see of you and to build the false image of yourself but this creates a kind of division within yourself of that which others know about and that which you’d rather hide from them out of fear you will be judged.

In our culture we demand that no one judges another but we do it all the time and judgement is a necessary part of growing and developing. Imagine education without anyone telling you when you get an answer right or wrong, the same is true of the development of character and behaviour. If you want to be a part of a society then you must act within the framework and worldview of that society, if you do not then you are not united in behaviour and outlook with those around you and the bonds are broken. Judgement helps us to connect with others and to learn how to live and behave with those around us.

The problem arises when mistakes and ‘failures’ are seen to be feared and resisted. This view leads to the inevitable hiding of faults and a desperate and futile attempt at being perfect in the eyes of others. Judgement, in this culture, becomes a devastating rejection of a person into the abyss of eternal damnation. The community portrayed within the Rule of St. Benedict, however, is one rooted and established on grace and a desire to be humbled (‘humiliated’ in the truest sense of the word.) With grace, mistakes and faults are to be expected and open to redemption by God who, when invited to, can cleanse us from all faults and make us perfect by his Spirit. Judgement, in this culture of grace, is seen as a diagnosis of a problem that is curable by the great Healer. The rejection of judgement is the resisting of full force of grace and healing within the Body of Christ.

In the issues of mistakes in the ‘mundane’ parts of communal life, St. Benedict is essentially saying in this chapter,

See above.

Although there is one difference in this chapter which has not been said in previous chapters,

If the cause of the sin is secret (hidden in the soul), the monk should confess to the abbot or one of the spiritual fathers. (my emphasis)

Throughout the Rule so far, the advice is to take confession to the abbot and he shall make judgement on the form and severity of correction. Here, however, there is the option of not going to the abbot but ‘one of the spiritual fathers’. When the fault is internal, i.e. not a tangible, which does not impact the community in a practical way, then the monk can go and admit it to another with authority granted to them by the abbot. This must be done, as with other sins, quickly before it becomes habitual or longer lasting.

This is characteristically practical of St. Benedict. I know that I have thoughts and temptations each day which pass, unseen by others, through my mind which effect my behaviour and attitude towards others. I can keep them private out of fear of being judged for thinking or feeling such things and no one would be any the wiser, their opinion of me would still be good and I wouldn’t upset or hurt them and thus cause them to reject me in some way. I justify the hiding of these mistakes by saying I don’t want to upset my brothers or sisters and cause them to act out of anger but it’s not the full truth.

In the Apprentice this year, one candidate made a mistake which cost the team dearly in the task. He was obviously ashamed of his failure and, instead of admitting it to the others, he ‘made a business decision’ and ‘for the morale of the team’ to not tell them: he lied. In the boardroom the truth came out and he continued to persuade the others, Lord Sugar and himself that it was solely for the morale of the team. I was surprised to hear, after he was ‘fired’, that others said this was a reasonable thing to do and was an established ‘technique’ in business. It was hiding in the darkness out of fear of the idol of himself he had made would crumble and he would be humbled.

Going to another and confessing the thoughts or inner sins stops us from building the idols of ourselves whilst, at the same time, protecting those who may not yet have the grace to forgive and pray for our healing from the mistake. The hearer of the confession may feel that the wisest thing to do in order to be healed is to go to others who may be affected by the inner mistake and admit it to them without involving others in the community. That other person may be the abbot and so it would be wise to time that admission for the danger is, the abbot still being human and able to fall themselves, might respond rashly out of anger or fear.

Sacred/Mundane

I had a good conversation with someone this week about the frustrations of church and they were keen to express their disappointment and anger at the irrelevance of church services to the majority of the population of this country. They had no problem with the Church, the people who make up the Body of Christ, but the worship services were a waste of time. I wonder whether the division between these two things is the problem here. What I mean is, if you don’t engage in the worship services of the Church then how do you engage with the other aspects of the Church’s life? You should have the same attitude when you go to a Sunday service (if your church meets on a Sunday) as you do when you meet together for social times because worship encompasses both activity/tasks and the devotion of time in the presence of God. God should be involved in all that we do, no matter where we are as individual disciples or with other Christians. We know this, so why is it that we say in one instance,

This particular group is my church.

and in another,

I don’t get that group of believers or how they express their faith (if indeed they have one)

The Church is the Church. It is, at it’s most basic level, a gathering of disciples of Jesus Christ. When we meet together we remind ourselves of the Body of Christ and we re-member Christ amongst us by his Holy Spirit. In this posture we humble ourselves before him and lay down our wills in favour of his and we worship, either by enacting his commands or proclaiming his greatness and majesty to position ourselves firmly beneath his will and command.

This should happen whenever we are with other followers of Jesus. Everything we say and do therefore should be worship in these two sense: reminding ourselves and each other of who we serve and to be humbled before him and also doing Christ’s work on earth/building his kingdom and not our own. The kitchen, cellar, garden, etc. then become places of worship because where ever we are we worship God.

If everywhere is sacred does this mean we no longer need specific places of worship? I would say that if we didn’t meet in one place we’d meet in another space and it would become sacred, therefore, we will always have specific sacred sites which we congregate in to intentionally praise and re-member Christ amongst us and receive from him. If we close our church buildings we’d need to find other buildings in which to meet for worship and if we moved we’d lose the connection with the two thousand year history and tradition of our faith and re-member with those ‘saints’ which have gone before.

Indeed, the whole of the worship service as passed down from generation to generation is a tool to connect with the saints throughout the ages to have relationship with the past, the present and the future. It is the mysterious work of God’s Spirit to bring us into the communion of Saints who will all stand, one day, in glory to sing God’s praises. Our worship services are, whether we feel it or not, a foretaste of this heavenly reality. We want to hold onto tradition, not because we are fearful of change, but because we want to honour our brothers and sisters before us and worship with them. It is a lesson we must heed in our time, to lay down our own preferences and choose to honour others before ourselves. This is painful and difficult thing to do because sometimes it feels like a one way street but we enter, in part, to Christ’s approach to us that when we were still sinners he came to meet us. He chose grace and became in the form of a servant and was obedient… to the point of death on the cross.

When we don’t appreciate the sacred in the mundane there is the danger that we will make the sacred, mundane. We stumble into our times of worship together and informality leads us to laziness and blindness. Samuel Beckett writes in his play ‘Waiting for Godot’,

But habit is a great deadener.(Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot (London: Faber and Faber, 2000) p.83)

We all find it easier to differentiate between ‘work’ and ‘life’; we talk of achieving the work/life balance but in the life of faith everything is work and everything is life. When you head into the office, the school or wherever you ‘work’ you do not leave your discipleship at the door. You’re going to that place with the mission of Christ ringing in your ear. The priority for disciples, over and above the job description, is to build God’s Kingdom here on earth, to make disciples, to be light in the world. In this mindset we approach worship as a duty that we feel forced to do in our ‘spare time’, there is then the pressure of making it beneficial and for us to feel something. When the service doesn’t live up to that expectation we reject it and complain and grumble. If we were to approach it with the knowledge that we should always be worshipping and encouraging one another as disciples then whenever we meet it is a joining in of what is going on in all of our hearts. Worship then is not the shop window of the community but the factory, the powerhouse at the centre. We return to this place of communal re-membering of Christ to be fed and to be sent out. Inviting people into the community is through the thresholds of the community and via the waters of baptism.

Reflection

This chapter is a bridge between two important points. We are moving from the discussion on the need for swift admission of faults and mistakes, firmly establishing an attitude towards judgement within the framework of grace and humility. We are moving to a discussion on the erasing of a sacred/mundane divide which protects us from the demands of discipleship. The establishing of a distinction between sacred and mundane is done for the same reason we find we want to maintain both light and darkness. In one we can do what we like and behave without judgement and shame whilst still being able to enter into the other controlling what others see and what they don’t.

Those who argue that darkness must exist in order to appreciate the light are trying to justify the maintaining of that small corner of our lives that is useful to feel comfortable and in control. The problem is, without the light reaching those parts we cannot appreciate the full force of grace which transforms and heals us to be the fully resurrected people of God. The Refiner’s fire must burn into every aspect of our lives and change us. This is a painful experience but until we go through it we cannot know the full brilliance of our God who we invite to lead us to holiness and peace.

Our communities must be rooted and established in grace. In this we intentionally seek to be humbled and then to see judgement in the right way as a means to be in the right position before our God who we worship in every aspect of our lives. This means to be actively seeking to be in right relationship with other Christians and trusting in the vehicle of grace: God’s Body, the Church.

If we are not channels of grace then we have no right to call ourselves church… The body of Christ the ultimate vehicle of grace. (John Barclay, a lecture on the wisdom of the cross in 1 Corinthians, Tuesday 4th June 2013, Diocese of York Clergy Conference)

Gracious and healing God, bring into light those things we long to keep hidden in the darkness. We invite your judgement onto us knowing that you are tender and loving towards those that fear you and you have come, in the person Jesus, to heal sinners like me. May our communities be places where mistakes and faults are dealt with quickly so we can experience more fully your grace and love for us.

Come, Lord Jesus.

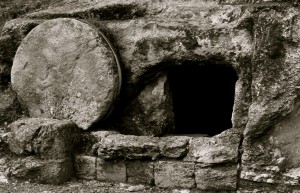

On Resurrection Sunday, I preached a sermon on the empty tomb and proposed that we can fall into the trap of staying at the empty tomb; we can get caught up in the empty tomb and be so amazed at it’s emptiness that we forget the real wonder of that day (This was an unashamed re-working of Thomas Merton’s reflection in his book ‘He Is Risen’). The empty tomb, I suggested, is just a signpost to the real thing. It is not the empty tomb we worship, it is the risen Lord. I likened this to gathering round a signpost for Yorkshire and celebrating as if we had arrived in God’s own country (I apologise to those heretics who do not accept this truth to be self-evident!)

On Resurrection Sunday, I preached a sermon on the empty tomb and proposed that we can fall into the trap of staying at the empty tomb; we can get caught up in the empty tomb and be so amazed at it’s emptiness that we forget the real wonder of that day (This was an unashamed re-working of Thomas Merton’s reflection in his book ‘He Is Risen’). The empty tomb, I suggested, is just a signpost to the real thing. It is not the empty tomb we worship, it is the risen Lord. I likened this to gathering round a signpost for Yorkshire and celebrating as if we had arrived in God’s own country (I apologise to those heretics who do not accept this truth to be self-evident!)