I finish this month, as Canon for Intercultural Mission and the Arts, having experienced an intense period of engagement in intercultural theory and practice. I helped to organise a conference of intercultural churches and then went into Holy Week where we, as a Cathedral, along with friends from other churches, spent some time each day out in City Park inviting people to talk about faith and Jesus. Both of these have caused me to ask questions about intercultural ministry and about the current evolving culture in the UK.

Back in July I wrote about Bradford (click here), exploring its history and drawing some suggestions as to what categorises something as ‘Bradfordian’ and, in part, also ‘English’. Of course, as with most historic study, there was a large amount of personal bias as to what sources I used and through what lenses I examined them. I received a number of personal responses from readers from Bradford who shared some of my conclusions particularly the questions raised about the opportunities afforded to us as City of Culture 2025.

I don’t want to rehearse those observations again but rather pick up on two points that I raised and further unpack them in light of my intense fortnight of intercultural ministry.

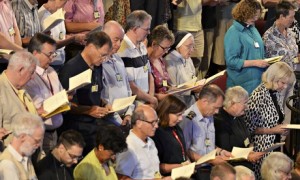

The conference was a gathering of self-selecting ‘intercultural practitioners’ in the Church of England seeking to network with others. The programme was packed with experienced and wise speakers ranging from academics to those engaged in intercultural practice. It was only the second such conference run by the emerging Anglican Network of Intercultural Churches (ANIC) of which I am on the steering group for.

The conference was funded in large part by the Racial Justice Task Group of the Church of England and, therefore, had a particular emphasis on racial justice. During our conversations, however, I started noticing a subtle and uncomfortable experience: it was rare that my culture, my ethnic heritage, my race, was talked about using positive language.

I understand that being ‘British’ or, worse, ‘English’ is problematic as we rightly face up to and come to terms with our colonial past and our own involvement in slavery and exploitation. I know that this work is important and critical if reconciliation, not just with fellow human beings but also with ourselves, is to be achieved. But, in a space where we were being encouraged to honour each other’s cultures and heritages, I did not feel as though that was being done for me, even by those advocating for such an approach. I found this curious.

As I say, this was done subtly; for example, as with all conferences, there was a timetable. This particular programme, in my mind, was overly tight and unrealistic. I attempted to raise the issue in a planning meeting but my view was dismissed and told that it would be fine. On the first day, however, the timings were in disarray before we had even welcomed people to the conference! We were running thirty minutes late and that impacted a whole lot of things. People from the front (from global majority heritage backgrounds) explained the situation by bringing out the cultural trope, “African time” or ‘South Asian time”; basically, relying on the understanding that “In Britain you have watches. In Africa we have time.”

As someone on the autistic spectrum, who struggles with ‘rules’ changing and who likes order and structure, particularly in regards to time, I attempted to accept this cultural difference but found myself feeling increasingly belittled when this cultural idiosyncrasy moved from a knowing joke to the insinuation that it was something that I needed a form of healing from. When I pointed out that there would be people arriving at the Cathedral for a service which they had graciously changed the time of to suit us, and that we were going to be half an hour late for, my concern was brushed away by an individual with a, “stop being so English.”

I have reflected before about how I feel when someone is late. Back in 2014 I wrote,

…it is not true that they’d rather be vacuuming a house than making the allotted time for meeting me but when you’re the one sat twiddling your thumbs, unable to start something in case you get interrupted, you can feel powerless to their ‘whims’. This is the problem with lateness: it is a power play. Lateness creates an imbalance in a relationship because one person refuses to be changed by the desire of another whilst the second party has committed and become beholden to the first.

CHAPTER 43: LATE-COMERS TO THE DIVINE OFFICE AND MEALS

The difference in timings is, due to my neurodiversity, a particularly challenging cultural difference for me. I don’t expect people to change their cultural approach to time to suit me but I found it hurtful when my embarrassing but instinctive sensitivities were dismissed completely by strangers. I tried to build relationship by being vulnerable and telling some key people that I had neurodiversity and tried to explain what it physically felt like when things are changed; the panic, the fear, the psychosomatic scratching on the inside of my head but they didn’t seem to understand.

I felt alone and frantic.

Of course, as I wrote back in 2014, different notions of time touches on power. As the dominant, ‘host’ culture (being in England) there is a social dynamic in all forms of hospitality and the different cultural approaches to it. I have begun to explore some of these over the last year in relation to working at a Cathedral where we welcome many different guests. For intercultural relationships to develop there must be a mutuality from both sides which is complex when, historically, one’s ancestors have abused such social bonds so profoundly. Much more work on reconciliation is required and that demands much deeper relationships built in safe spaces. I am in favour of ‘Lament Into Action’ but I am unconvinced we have a vision for a fuller, more holistic and prophetic approach to lament, leaving any action hindered in its efficacy.

My familiar neurodivergent response to timekeeping was not the only reason this seemingly petty example was ‘uncomfortable’. The more subtle and disturbing experience was the unbalanced negativity towards white people that appeared at moments during our discussions. This is where more exploration on lament is needed.

One white, male speaker was told that he only mentioned his whiteness four times in a fifteen minute presentation and one of them was not used to critique its impact on others. I was baffled by this comment. I wasn’t sure what the point was and what the error had been on the speaker’s part. On another occasion a Nigerian speaker, who spoke powerfully on intercultural churches as a framework for truth, justice and reconciliation, suggested that Anglicanism continues to be used to extend ‘Englishness’. That was a perceptive and challenging point that deserves fuller unpacking, but it was his response to a question which made me concerned. The question was:

Can you name a positive attribute of Englishness and a then name a negative attribute of Englishness?

Now, he may have misheard or misunderstood, but he began his answer by naming a positive to the Church of England. His salient point about Anglicanism (of which the Church of England is a leading part) being an extension of Englishness may have been in his mind but he never gave a positive attribute to Englishness. I’m not suggesting that he was consciously avoiding the question but it went to highlight my sense that no one had spoken positively about what white, English culture brings to the intercultural party. This can lead to some white, English people (particularly men) feeling shame with no way of moving through that due to the unchangeability of their race or biological sex. This is, many are arguing, in part, a reason there is a tangible growth in more nationalistic, far-right sentiment in England today. The only seeming chance of hope is found in escaping the perceived imbalance of lament, or, rather, the perceived forcing to lament of one by another. The increasingly common response to the ‘woke agenda’ and the sometimes heavy-handed attempts to encourage lament is defensiveness, a refusal to participate and a retreat from relationship. This creates the intractable silos of polarisation.

Which brings me to Holy Week witness in Bradford city centre.

Standing outside, often in the cold and rain, on a lunchtime in our city centre, with a large wooden cross, singing hymns, reading the Bible and delivering a short talk on the importance of Holy Week for Christians was always going to be a tough task. I was surprised by the small number of people who had genuine conversations of faith. For each of these, however, we were also met by aggressive, baffled and insulted faces by many. The act of witness seemed to make many feel uncomfortable. There was a weary revulsion palpable by the passerbys.

Of the people who did stop and talk, many of them were clearly in mental distress, intoxicated or disproportionally aggressive and white. I was spat at, threatened, asked impossibly complex questions about conspiracy theories (“Why has God given me the message ‘1661’ in the clouds?”).

On Thursday it was my time to give a short reflection aimed at inspiring discussion on the topic of Jesus and the cross. Over the previous three days I had watched others attempt to do this in various different ways. Despite their best efforts, nothing seemed to be hitting the mark. I put it down to the context or to the weather but there was something more; something deeper.

I began my public reflection by saying that “talking about personal things, such as faith, is difficult and painful in this place and at this time.” Bradford has a history of conflict in inter-racial, multiethnic, interfaith relations. The riots of 2001 still loom heavy over the social story of our city and the undercurrent of suspicion has not shifted completely. What I was sensing during Holy Week was a return of these hostilities and our innocent presence in the public square was clearly skirting too close to this reemerging reality. In my talk I wanted to name that. To ignite a prophetic imagination in a people to dream and to hope of a better future one must start by acknowledging and lamenting the current state as fully as possible. For something to be healed it must be diagnosed and brought into the light. I wanted to start conversations with the unspoken: the aggression (fight response), the fearfulness (flight response) and the apathy (freeze response) in order that we might seek healing and redemption there. I wanted a shared sense of lament to all aspects of the breakdown in social relationships and trust between us all and to share in the healing together. Like Jesus did by taking on our humanity and reconciling himself to us in his death.

At the conference I tried to do the same thing. I was asked to speak on racial justice and I began my seminar by acknowledging the conflict within me; on the one hand a right sense of the optics of a white man leading a session of people mainly with global majority heritage and on the other a profound sense of how many white people excuse themselves from this important conversation. What was so uncomfortable about my observation of the reluctance to speak positively about Englishness was the unspeakable yet understandable and palpable distrust and unresolved trauma we all are feeling on both sides of the racial differences. I am inspired by Óscar Romero’s words.

Liberation that raises a cry against others is no true liberation. Liberation that means revolutions of hate and violence and takes the lives of others or abases the dignity of others cannot be true liberty. True liberty does violence to self and, like Christ, who disregarded that he was sovereign, becomes a slave to serve others.

Óscar Romero, ‘The Violence of Love‘ (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1988) p.40

How do we constructively work towards intercultural relationships? How do we name the complexities of gifts both honoured and unwanted that we all bring to such relationships?

Two words: prophetic imagination.More on that next time.

Who has the right to the land of Gaza and the West Bank? We could start by going into all the history and legalities over this issue. The use of words such as ownership can then be brought into question. Historical facts could then be muddied by interpretation of events and phrasings and then there’s the insurmountable obstacle of personal stories and the tangled web of historical violence from both sides.

Who has the right to the land of Gaza and the West Bank? We could start by going into all the history and legalities over this issue. The use of words such as ownership can then be brought into question. Historical facts could then be muddied by interpretation of events and phrasings and then there’s the insurmountable obstacle of personal stories and the tangled web of historical violence from both sides. Winning arguments is easy if you can just wear down your opponent and the easiest way to do that is keep moving the goal posts; re-define the terms of the argument until it gets too complicated and they get confused and worn out. You don’t need truth to do this; all you need is stamina and intelligence.

Winning arguments is easy if you can just wear down your opponent and the easiest way to do that is keep moving the goal posts; re-define the terms of the argument until it gets too complicated and they get confused and worn out. You don’t need truth to do this; all you need is stamina and intelligence. In November 2012 General Synod’s motion to vote female bishops failed, only just but enough. What was clear back then was that the debate had been established on the principle that there was an ‘us’ vs. ‘them’. The aim was not to discover wisdom but to ‘win’ at any cost. Both parties on the extremes didn’t seem to care how they would win just as long as they did. This week, however, the tone of the debate was not on winning points and persuasion but a genuine, heartfelt desire to seek wisdom and to trust one another. The debate stopped being about party politics but more about seeking genuine peace and wisdom only found in the Spirit of God.

In November 2012 General Synod’s motion to vote female bishops failed, only just but enough. What was clear back then was that the debate had been established on the principle that there was an ‘us’ vs. ‘them’. The aim was not to discover wisdom but to ‘win’ at any cost. Both parties on the extremes didn’t seem to care how they would win just as long as they did. This week, however, the tone of the debate was not on winning points and persuasion but a genuine, heartfelt desire to seek wisdom and to trust one another. The debate stopped being about party politics but more about seeking genuine peace and wisdom only found in the Spirit of God. To dismantle such a fence of division takes time, building trust and relationship something sadly lacking in our politics in this country. My very public critique of the Same Sex Marriage Bill was not based on some personal, moral judgement on homosexuality but on the way a decision was being sought. It was rushed. The lobbyists pressured opponents with the supposed lack of time and bullied people into making a response; to choose a side of the fence. Rather than taking the fences down they were happy to keep them there. People were forced off the fence onto one side or the other and it was all done by the manipulation of language. The same is being done with The Assisted Dying Bill.

To dismantle such a fence of division takes time, building trust and relationship something sadly lacking in our politics in this country. My very public critique of the Same Sex Marriage Bill was not based on some personal, moral judgement on homosexuality but on the way a decision was being sought. It was rushed. The lobbyists pressured opponents with the supposed lack of time and bullied people into making a response; to choose a side of the fence. Rather than taking the fences down they were happy to keep them there. People were forced off the fence onto one side or the other and it was all done by the manipulation of language. The same is being done with The Assisted Dying Bill.