While on retreat before his consecration to episcopal office in 1970, Óscar Romero, wrote, ‘My consecration is synthesized in this word: sentir con la iglesia.’ Eight years later, as Archbishop of San Salvador, Romero found himself facing heavy criticism from the Church. He wrote, in a letter justifying his position to the established Church, ‘For many years my motto has been “Sentir con la Iglesia.” It always will be.’

To write on the life of Óscar Romero, is to write on the nature of conversion. It is on this singular topic that Romero returned most frequently throughout his long ministry. It is also his own, supposed ‘conversion’ that every biographer rightly focuses on and explores. The infamous story of the murder of Fr. Rutilio Grande, a Jesuit priest and long-time friend of Romero, twenty days after taking up the role of archbishop clearly had a profound effect and is often depicted as ‘Romero’s road to Damascus.’ To what extent, however, did that moment change Romero?

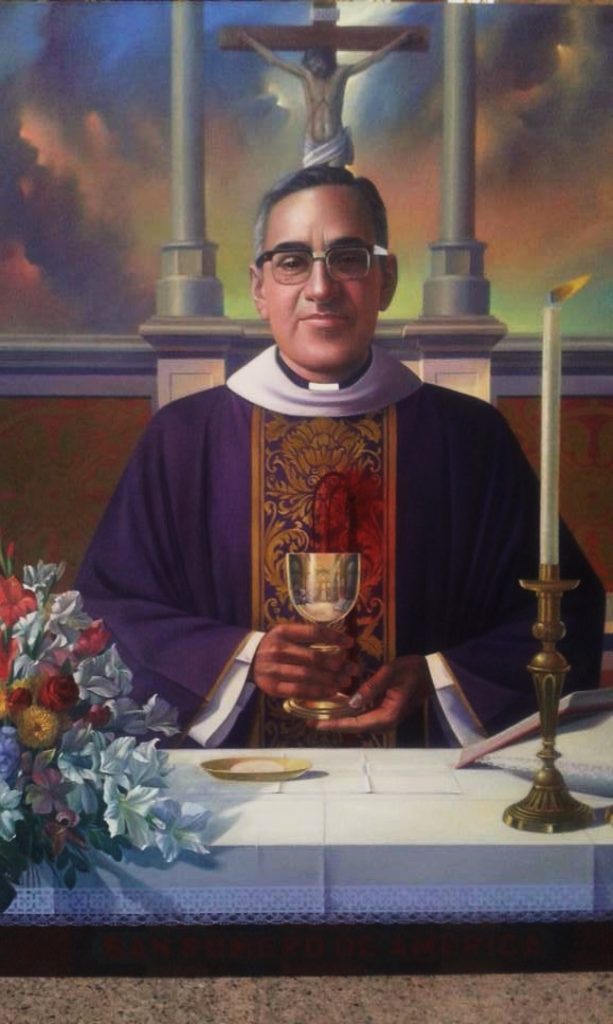

In the literature about Romero, the way that his change is described reveals much about how the entirety of his legacy gets accounted for. Consider three images of Romero. The first is the caricature perpetuated by his opponents: he was a weak and confused churchman who became a puppet of radical priests and communists ideology… the sudden and radical transformation of a right-wing bishop who becomes a revolutionary spokesman for justice, to a tamer notion of a churchman who responded with the same Christian faith he always possessed but in a new, highly charged situation.

Michael E. Lee, Revolutionary Saint: The Theological Legacy of Óscar Romero (New York: Orbis Books, 2018) p.49

Each biographer must navigate and select which of these seemingly competing views will be the lens through which they read the life and work of this complex figure. It is not, primarily, my intention to rehearse these different voices and tell this particular story again. I merely want to juxtapose those voices and add in Romero’s own to explore how one who is depicted as having been so dramatically transfigured can still be seen as the same person faithfully holding to the same ideal.

It is telling that so much is made of the supposed conversion of Romero and how it has been viewed by different parts of the Church in order to claim this man’s legacy as their own. Rodolfo Cardenal points to ‘three duelling versions of Romero: the nationalist, the spiritualist, and the liberationist’ Many would state that Romero was converted, as all conversions are traditionally seen as, from one place to another; from conservative to progressive, from neo-scholasticism to Liberation Theology, from timidity to prophetic but Romero consistently denied this view.

I denied having used the phrase attributed to me of “having been converted” and much less having compared myself to other bishops or vainly believing myself “a prophet.” What happened in my priestly life, I have tried to explain to myself as an evolution of the same desire that I have always had to be faithful to what God asks of me.

Óscar Romero, letter to Baggio, June 24, 1978, The Brockman Romero Papers

As he set out on episcopal ministry in 1970 through to his assassination ten years later, Romero stated he followed the Ignatian maxim sentir con la iglesia. I want to explore each of these ‘conversions’, the different ‘duelling versions’ presented in them and ask how Romero remained ‘faithful’ throughout. I will continue to return to Romero’s own voice and seek to present my conjecture: Óscar Romero embodies the Church at time of evolution, more than the popular, political revolution of society that he is heralded as a prophet for.

Sentir con la Iglesia

The Church, then, is in an hour of aggiornamento, that is, a crisis in its history. And as in all aggriornamenti, two antagonsitic forces emerge: on the one hand, a boundless desire for novelty, which Paul VI describes as “arbitrary dreams of artificial renewals”; and on the other hand, an attachment to the changelessness of the forms with which the Church has clothed itself over the centuries and a rejection of the character of modern times. Both extremes sin by exaggeration… So as not to fall into either the ridiculous position of uncritical affection for what is old, or the ridiculous position of becoming adventurers pursuing “artificial dreams” about novelties, the best thing is to live today more than ever according to the classic axiom: think with the Church.

Óscar Romero, “Aggiornamento”, El Chaparrastique, no. 2981, January 15, 1965, p.1.

The above quote, written years before his consecration, sees the first recorded instance of Romero writing about of the Ignatian ‘axiom’ that came to define his life and ministry. Sentir con la iglesia is used here to describe a seeming middle way that helps to protect the Church from falling foul of two extreme errors; a feature we will return throughout. The question one must answer first is: what does sentir con la iglesia mean?

Sentir con la iglesia is the object of a set of rules placed at the end of the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius. In the Latin Vulgate edition the opening remark is translated as ‘Some rules for observing how to feel with the Orthodox Church.’ In another translation it reads, ‘The following rules should be observed to foster the true attitude of mind we ought to have in the Church.’ Much has been written and explored on the complexities of translating sentir con la igleisa. Again, I will not replicate the old arguments, suffice to say George Ganss notes that the rules to ‘think with the church’ ‘involves far more than the realm of thought or correct belief.’ All would agree that sentir encapsulates a thinking, feeling, listening and embodying with and in the Church. Douglas Marcouiller SJ summarises it well.

To think with the Church is not a matter of the head alone. It is a personal act of identification with the Church, the Body of Christ in history, sacrament of salvation in the world. To identify with the Church means to embrace its mission, the mission of Jesus, to proclaim the Reign of God to the poor. To think with the Church is therefore an apostolic act… for Romero, to think with the Church meant not to think with “the powers of this world.” Romero listened to them, talked with them, but refused to align himself with them.

Douglas Marcouiller SJ, “Archbishop with an Attitude”, Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits, issue 35, no.3, May 2003, p.3

Before turning to explore the ‘duelling versions’ of Romero, let us return to his episcopal commitment in 1970. He expands his simple synthesis with a pledge to the magisterium.

My consecration is synthesized in this word: sentir con la iglesia. This means I will make the three ways of the church according to the encyclical Ecclesiam Suam my own and after examining my personal reality according to the criteria of the glory of God and the eternal health of my soul.

Óscar Romero, “Cuadernos espirituales”, entry for June 8, 1970

Ecclesiam suam was published whilst the Second Vatican Council was still deliberating but outlines an ecclesiological shift later fleshed out in Lumen gentium. In the early part of the encyclical, Pope Paul VI outlines three principles ‘which principally exercise Our mind when We reflect on the enormous responsibility for the Church of Christ.’ These three principles are: deeper self knowledge, renewal and dialogue. In his spiritual notes on these principles, Romero sketched out how he would live them out in his episcopal ministry.

The first, a deeper self knowledge, meant a commitment to ‘know[ing] the church more each day and my place and duty to her.’ Romero’s vicar general, José Ricardo Urioste believed ‘He [Romero] was the man in this country who best knew the magisterium of the Church, and no one since then has known it as well.’ This will be explored when we look at the proposed conversion from conservative to progressive. The second, the need for renewal, draws from the recurring theme in Romero’s ministry, ‘The church demands holiness and is always in need of conversion. I will be before I act. I have examined the many things that ask for penitence, caution, and reform within me.’ Here we will continue to explore the renewal the Church went through during Romero’s ministry and how he incarnated that within him personally.

Finally, the demand for dialogue. Here we touch on a particular point of contention when observing the conflicting interpretations and adoptions of Vatican II theology; that is of the place of the Church in the changing world. Although we will explore it briefly before, this also raises questions about Romero’s character and whether he converted from being timid to being a prophet, speaking out against established power and being ‘manipulated’ by left-wing, Marxists with in El Salvador.

From Conservative to Progressive

The terms ‘conservative’ and ‘progressive’, in the current time of highly polemical politic, have become satirical caricatures used to white wash opponents. In the current discussion, and in relation to Romero, ‘conservative’ is an erring towards the more traditional views, in this case, of the Roman Catholic Church and to be ‘progressive’ is to tend towards new ideas which push towards a change of ecclesial theology. For brevity I want to focus on Romero’s relationship with the dramatic changes that were taking place during and after Vatican II.

The Second Vatican Council was an historic moment within the Roman Catholic Church but still there are many who argue about the correct interpretation and application of the results. Michael E. Lee points out that there emerges two emphases; those who see ‘“continuity” or “renewal” against those who stress “discontinuity” or “reform.”’ Interestingly, the different interpretations of Vatican II are the same applied to Romero in its aftermath.

In his surprising announcement of an ‘Ecumenical Council of the universal Church’, Pope John XXIII stated, ‘In an era of renewal,’ recalling ancient forms of doctrinal affirmation and wise orders of ecclesiastical discipline ‘yielded fruits of extraordinary efficacy, for the clarity of thought, for the compactness of religious unity, for the liveliest flame of Christian fervour that we continue to recognise.’ It was for very conservative reasons that this momentous council was called at a time of great ‘progress’. Under the subsequent pontiff, it took a decidedly different turn, as we have seen in the encyclical Ecclesiam Suam, focusing on ‘renewal’ but even then, based on a deeper knowledge and faithfulness to the Church’s continuous teaching throughout history.

Romero was ordained prior to Vatican II and so saw the changes as they occurred in history. All personal accounts of the ministry of Fr. Romero are of a faithful, pious priest who loved people and was committed to the pope. It is not, therefore, inconceivable to interpret the life of Óscar Romero as one who embodies the Church at a time of great change, particularly in the progressive demands in El Salvador, his own context.

A pastoral letter, ‘The Holy Spirit In The Church’, written by Romero as bishop of Santiago de María in 1975, is more conservative than the ones written later when we he was archbishop, but there is a characteristically Romero trait found in it that echoes throughout his life and ministry.

Every renewal will be authentic when it favours greater bonding of the hierarchy with the community, when it achieves better communication of the true faith, and when it makes better use of the sacraments and other channels of grace. Adopting any doctrinal or pastoral approaches that neutralise, obstruct, or render ambiguous one or another of these three coordinates will mean working in vain or sowing confusion, no matter how brilliant or up-to-date such approaches may appear.

Óscar Romero, “The Holy Spirit in the Church”, May 18, 1975, p.4

This balancing between two extreme positions reveals a synthesis that perfectly portrays the Transfigured Christ, both human and Divine, in one moment. Romero himself calls this synthesis, sentir con la iglesia. We also see it in Romero’s editorial in Orientacíon in 1973, as he responded to the ‘progressive’ Medellin document,

An event in the life of the Church, so transcendental for the Americas, has been disfigured by the exaggeration of two extremes: those who do not want to allow themselves to be led by the vigorous breath of the Holy Spirit that impels the Church to a more dynamic presence “in the current transformation of Latin America,” and those who want to accelerate that dynamism so much that they have confused the exigency of the Spirit with the spirit of an anti-Christian revolution. The former and the latter have done much damage to the true spirit of Medellin that, before all else, is a religious spirit.

Óscar Romero, “Medellin mal comprendido y mutilado”, Orientacíon, no. 2030 (August 12, 1973), p.3

What we see here, even before his arch-episcopal ministry, is a call to embrace the ‘progressive’ but without denying the ‘conservative’ and vice versa. Again, the interpretation of Medellin is projected on to Romero and one’s analysis of Medellin will lead to a particular view of Romero himself. The proof often cited for Romero’s conservatism is his noteworthy dedication to the Pope and his fascination with ecclesial documents and encyclicals that he continuously quoted. Edgardo Colón-Emeric sees ‘his persistent appeal to ecclesial documents in his teaching and preaching’, that continued throughout his life, ‘is an expression then of his sentir con la iglesia.’

From Neo-Scholasticism to Liberation

Romero himself, in an interview during the 1979 Puebla Conference in Mexico, reflected ‘St. Ignatius’s ‘to be of one mind with the Church’ would be ‘to be of one mind with the Church incarnated in this people who stand in need of liberation.’’ This embodied interpretation of sentir may well, for some, prove a conversion in Romero’s understanding from a spiritualised, neo-scholastic ecclesiology to an incarnational one characteristic of Liberation Theology and there might well be some veracity to this view. Certainly in his pastoral letter, ‘The Holy Spirit In The Church’, his ecclesiology is notably more hierarchical and traditional than later letters, but there are still foretastes of his more articulated idea of the Church as ‘The Body Of Christ In History’ . This later, more incarnational ecclesiology is still rooted, as is all of Romero’s theology, in the magisterium, and the earlier pastoral letter is rooted in Vatican II with its re-emphasis of the people of God and it even shows some signs of reflecting on the Medellin documents to which Romero was beginning to adopt.

Lee makes much of Romero’s training which, at the time, was drenched in neo-scholasticism and presents the Salvadoran priest as the epitome of this heritage. Although Romero, undoubtedly, was greatly influenced by his time in Rome, we must not forget that he trained in the Jesuit institution and, as Jon Sobrino notes, ‘he used to recall his humble origins.’ By the time Romero is archbishop it is difficult not see him as a supporter of some forms of Liberation Theology. This conversion, like that from conservatism to progressivism, is a matter of positioning.

…a central point of contention in remembering Romero’s legacy: judging whether he represents Vatican II’s theology, liberation theology, both, or something else altogether depends a great deal on how those positions are identified.

Michael E. Lee, Revolutionary Saint: The Theological Legacy of Óscar Romero (New York: Orbis Books, 2018) p.2

Lee does agree that Romero should never be presented as one who ‘lamented the loss of preconciliar identity; but given his rigorous neo-Scholastic formation, one can inquire as to the kind of reception he gave the council and its documents.’ These enquiries though will show, as already stated, that Romero remained faithful to ‘think with the church’ including being wed to ‘the hierarchical communion’ of the Church but it is a misreading of his earlier work to suggest that that ‘Romero’s understanding of church authority was changing.’ Romero’s faithfulness to the hierarchical Church not only means that of the power from the top down but also from bottom up.

Edgardo Colón-Emeric presents a thorough depiction of the many forms of Liberation Theology describing them all as a direct response to Vatican II which, don’t forget, was called to conserve Church teaching in a new context. It is in this context that Colón-Emeric presents Romero as a Church Father. He turns to José Comblin’s identification of common traits that characterize church fathers: ‘a holy life, an orthodox faith, an understanding of the signs of the times, and popular recognition. The church fathers were not academic theologians but pastors (or monks) dedicated to edifying the church.’ It was to these Fathers that the Church turned to in Vatican II and I would side with those presented by Lee as seeing the ‘reform of Vatican II’ as the church changing ‘to be more traditional.’

Before moving onto Romero’s character, it is worth concluding that his renewal of theology and shifts in articulation, particularly of ecclesiology throughout his ministry does show some development and change. This, I am arguing, is in line with Colón-Emeric’s view.

In all, Romero understood that only to the extent to which he experienced the renewal of his passions and actions could he be identified with a church that was also in a constant process of renewal.

Edgardo Colón-Emeric, Óscar Romero’s Theological Vision: Liberation and the Transfiguration of the Poor (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2018) p.188

From Timidity to Prophetic

The incident of Fr. Rutilio Grande’s death was seen to embolden Romero ‘to accept a larger, prophetic role as the voice of the Salvadoran people’ and ‘turned the conservative, timid, bookish bishop into a flaming prophet.’ Arturo Riveria Damas, Romero’s successor, agrees.

Before the body of Fr. Rutilio Grande, Monseñor Romero, on his twentieth day as archbishop, felt the call of Christ to defeat his natural human timidity and to fill himself with the intrepidness of the apostle.

Arturo Rivera Damas, in the preface to Jesús Delgado, Óscar A. Romero: Biografia (San Salvador: UCA, 1990) p.3

Romero’s vicar general, however, portrays a different view.

[In the pulpit] Romero was transformed… Monseñor was a bit timid. In conversations in informal groups he hardly said anything at all… But when he got to the pulpit he was another man.

José Ricardo Urioste, interview, 7 December, 2002, cited in Douglas Marcouiller SJ, “Archbishop with an Attitude”, Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits, issue 35, no.3, May 2003, p.36

We capture something of that timidity in his notes prior to consecration in 1970 and see the desire seven years prior to the ‘conversion’ moment to evolve.

The church becomes self-aware and is renewed not for itself but rather to be attractive and bring redemption to the world. Being in order to act. I too need to be apt for dialogue with men…I will contribute my opinion. I have the courage to intervene… I will consult.

Óscar Romero, “Cuadernos espirituales”, entry for June 8, 1970

Romero is portrayed by many, particularly those closest to him, as an archbishop who listened to the people. In the introductory remarks of his final pastoral letter, ‘The Church’s Mission and the National Crisis’, Romero articulates this importance of dialogue.

Taking account of the charism of dialogue and consultation I wanted to prepare for this pastoral letter by undertaking a survey of my beloved priests and of the basic ecclesial communities… we must never think of the various responses to which one single Spirit gives rise as being at odds with one another. They have to be seen as complementary and all beneath the watchful overview of the bishop.

Óscar Romero, Joe Owen (trans.), “The Church’s Mission and the National Crisis”, Fourth Pastoral Letter of Archbishop Romero Feast of the Transfiguration, August 6, 1979, Archbishop Romero Trust, http://www.romerotrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/fourth%20pastoral%20letter.pdf, p.3 and 36

It was this dialogue that informed his homilies, the greatest testament to his theology, much like the Church Fathers to which we have already compared him. These homilies were examples, many of his later supporters have argued, to Romero being ‘the voice of the voiceless’, but it worth noting ‘Romero never arrogated that title for himself personally.’ He did, however, assume this role ecclesially. Quoting Lumen Gentium, Romero states ‘the holy people of God shares also in Christ’s prophetic office … under the guidance of the sacred teaching authority.’ Earlier in his ministry Romero stated

The pastor’s role is simply to raise his voice and summon people to loving responsibility, so that rich and poor love one another as the Lord commands (Jn 13,34), “because the strength of our charity is neither in hatred nor in violence” (Paul VI, 24-VIII-68).

Óscar Romero, Joe Owen (trans.), “The Holy Spirit in the Church”, First Pastoral Letter of Bishop Romero Feast of Pentecost, 18 May, 1975, Archbishop Romero Trust, http://www.romerotrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/lost%20pastoral%20romero.pdf

This ‘prophetic’ ministry was merely a continuation of his hierarchical understanding of the Church that he embodied and with which he thought felt and listened to. Marcouiller summarised it perfectly when he wrote, ‘The teaching of the Church called him to put himself on the line, to overcome his natural timidity, to identify himself with the church, the people of God, the Body of Christ in history.’ My conclusion, therefore, is that Romero continued in the Church’s duty, ‘to lend its voice to Christ so that he may speak, its feet so that he may walk today’s world, its hands to build the kingdom, and to offer all its members ‘to make up all that has still to be undergone by Christ.’’

Conclusion

Romero, remained, throughout his ministry, a faithful servant to the unity of the Church. He continually articulated the need to avoid the ever-diverging extremes and sought to unite them within the Body of Christ. A desire that finally ripped him apart. It is this understanding of sentir con la iglesia that I have tried to present here; a Church not solely of the magisterium but of the people, the Body of Christ in history. This church is both conservative and progressive, neo-scholastic and liberational.

The danger of any movement lies in going to extremes: either too much activity or too much spiritualism. There must be a balance between prayer and work for one’s neighbour.

unreferenced in Roberto Morozzo Della Rocca, Oscar Romero: Prophet of Hope (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 2015) p.123

To think with the church, then, was an evolving task. Colón-Emeric writes, ‘Sentir con la iglesia is not a point of departure for Ignatian spirituality but its point of arrival.’ This language, however, presents it in too static a way rather than dynamism with which Romero himself experienced it.

St Ignatius would present it today as a Church that the Holy Spirit is stirring up in our people, in our communities, a Church that means not only the teaching of the Magisterium, fidelity to the pope, but also service to this people and the discernment of the signs of the times in the light of the Gospel.

Óscar Romero, originally in Enrique Nuñez Hurtado, Ejercicios esprituales en, desde y para América Latina: Retos, intuiciones, contenidos (Torreón, Mexico: Casa Iñigo, 1979), this translation by James Brockman, “Reflections on the Spiritual Exercises”, The Way, no.55, Spring 2986, p.102

Whatever conversion, renewal, evolution Romero experienced throughout his life seems to always occur at the same time as the Church to which he was devoted. It is significant, as I have repeated, that the same depictions of Romero from the various wings of the Church, mirror the exact same portrayals of the Church itself. In this way Romero faithfully embodied the Church, throughout his life, and in so doing is seen to evolve to suit the new context in which Christ is invited to work, speak and work.